Smart Prosperity’s Research Network conducts world-class research focused on a stronger, cleaner economy. This Spotlight Series highlights the activities of faculty and student researchers alike, showcasing the breadth of expertise and activities of our Research and Student Networks.

In this edition, we caught up with Diane-Laure Arjaliès, Michelina Aguanno, Celina Chen, Melanie Issett and Baani Mann. The team was awarded funding through Smart Prosperity’s 2020 Call for Research Proposals for their project titled “The Opportunity for Conservation Impact Bonds to finance investment in conservation and enhancement of natural capital in Canada“.

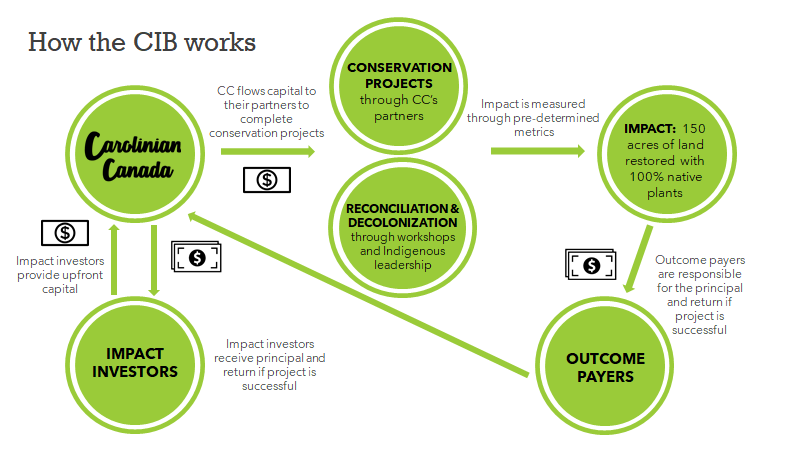

A Conservation Impact Bond is an outcomes-based financial instrument focused on reconciling peoples and ecosystems through the processes of conservation, restoration, reconciliation, and decolonization. It is similar in structure to social impact bonds, including a facilitator, investors, and outcome payers. The particular Conservation Impact Bond we are studying is the first-of-its-kind in Canada, and is facilitated by Carolinian Canada, a non-profit conservation network based in London, Ontario. In the first phase of the Conservation Impact Bond, a social finance firm provides the upfront investment, and a multinational company acts as the outcome payer, paying out the principal and return of the Conservation Impact Bond if the desired metrics are achieved. Metrics are determined collaboratively through impact assessment and decolonizing workshops with all partners including habitat partners, Indigenous communities, investors, and others. The figure below illustrates the various components of the Conservation Impact Bond model.

The “big picture” questions that we are trying to answer include:

The Deshkan Ziibi Conservation Impact Bond is located in Southwestern Ontario’s Carolinian life zone that extends from Windsor to Toronto. This ecoregion provides a unique setting for our work as it is simultaneously home to some of the country’s most diverse flora and fauna and supports 25% of Canada’s human population on only 0.25% of Canada’s landmass (Crins, Gray, Uhlig, & Wester, 2009). Over the last two centuries, approximately 85% of the ecoregion has been converted to cropland, pasture, and urban development, resulting in the region being home to many species at risk and being identified as the most imperiled in Ontario (Crins et al., 2009). This ecoregion’s biodiversity potential coupled with the large-scale human activities in this region represents an ideal space for us to launch a Conservation Impact Bond that is aimed at improving the coexistence among humans and wildlife. This financial instrument aims to engage diverse sectors, partners, and worldviews in the region to promote native habitat restoration and conservation, reverse the trends of biodiversity loss, and reconcile human-nature relations.

Yes, through our work we have identified a number of obstacles and tensions. We will discuss two main ones here.

One conflict that we have faced is around the extension of market thinking and market valuation into a sphere of life previously governed by non-market norms (Sandel, 2012). Combining the use of a financial instrument with the valuation of nature has been a challenge in the Conservation Impact Bond model. On one hand, financial instruments, like bonds, need financial indicators to operate in the sector. On the other hand, nature is not traditionally valued in monetary terms and efforts to do so are largely contested. How much is a native species worth? How much is an ecosystem that supports life worth? How much does biodiversity loss cost the economy? In an effort to reconcile these tensions, we have developed a holistic evaluation process that aims to align with research out of organizations such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES, 2019) to put into practice plural valuations that capture and create space for the diverse sociocultural, economic, and ecological factors involved. As a result, the bond’s success is evaluated using both quantitative and qualitative metrics that aim to be inclusive of diverse perspectives and worldviews.

Another challenge that we have faced with this bond is deconstructing some of the underlying colonial tones that come with the financialization of nature. The goal is to provide an instrument that seeks to align seemingly disparate worldviews and diverging motivations for conservation to leverage the common goal of natural habitat restoration. Consequently, metrics used for the bond are community-based and encompass Indigenous perspectives, in order to consider aspects specific to each community that it is engaged with. This means the bond is able to go “deep” rather than “wide,” but scaling may prove to be a challenge.

France started to work on sustainable finance ten years before Canada and is therefore more advanced when it comes to the integration of non-financial criteria into mainstream investment practices. The delay in Canada can be notably explained by the complex relationships between Canadians and the oil sands. For a long time, Canadians worried that sustainable finance would mean excluding companies belonging to the energy sector.

But Canada is catching up very quickly. In 2019, the Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance published a very interesting report on the role of the financial sector in the transition of the country towards green economy. The federal government has also outlined clear environmental priorities in its 2021-2025 budget, with a goal to conserve 25 per cent of Canada’s lands and oceans by 2025. This indicates that the country has now understood the importance of investing in green infrastructure and nature-based climate solutions, particularly in the post-COVID recovery. Yet this objective cannot be achieved without the support of financial markets. Conservation Impact Bonds, such as the one we have developed in this community-based research project, could definitely be part of the solution.

The very existence of human and non-human life on our planet relies on the functioning of our biosphere. Business is not immune from this truth. Thus, responsible stewardship of our biosphere is, in fact, “good business.” A background in business education has provided us with a foundational understanding of the language, scale, and power that the business world holds domestically and in global affairs. Additionally, the sustainability and impact-focused courses offered at the Ivey Business School, including programs such as the HBA Sustainability Certificate, helped to expose us to the work that is being done at the intersection of business and sustainability all over the world. These classes really pushed us to think critically and helped to demonstrate that business and environment health do not have to be opposing forces and could, instead, be mutually enhancing. Having this background has enabled us to think innovatively about how we can leverage business strategies and tools towards the achievement of more just and sustainable social and environmental outcomes.

We believe that involving business is crucial to addressing the major environmental issues of our time. Businesses hold a lot of power in how our society currently operates and this provides them with the capacity to support and drive the transformational changes that are required today and in coming years to keep global warming below 1.5C. In order to tackle the grand environmental challenges of our time, businesses must rise to the challenge and take responsibility for their role in restoring and maintaining the life-support mechanisms of our biosphere for current and future generations.

Celina and Baani: After graduating business school, we are both set to work in consulting. However, we believe business leaders need to be environmentally aware and even environmentally motivated to ensure that our Earth is habitable for future generations. As such, we hope to continuously merge business and sustainability throughout our careers.

Melanie: I’m planning to attend the Sustainable Management Master’s program in the School of Environment, Enterprise, and Development at the University of Waterloo to further my studies on the intersection between environment and sustainability, and business and development.

Michelina: I am pursuing a PhD at Ivey School of Business in the discipline of Sustainability. I am currently researching the valuation of nature and the relationship between land ownership and biodiversity.

Diane-Laure: I’ll be busy continuing my work on conservation finance and the Deshkan Ziibi Conservation Impact Bond!

Thank you, Diane-Laure, Michelina, Celina, Melanie and Baani!

For more on the Smart Prosperity Research Network, click here. For recent Working Papers produced by the Research Network, click here. For other Researcher Spotlights, click here.