Resilient Leadership: Strengthening Teams in Times of Uncertainty

In this episode:

In a world of constant disruption, resilience isn’t just about bouncing back—it’s about adapting, leading, and sustaining high performance under pressure. In this episode produced as part of Global Ivey Day 2025, we explore psychology of resilience at both the personal and team levels, focusing on how leaders can foster a culture of adaptability and sustained well-being.

Drawing on cutting-edge research in organizational behaviour and leadership, our expert panel shares practical strategies to help leaders navigate uncertainty, build trust, and empower teams to thrive—even in the face of adversity. Whether you’re leading through economic shifts, industry upheaval, or everyday challenges, this conversation provides actionable insights to strengthen your leadership and the resilience of those around you.

Guests:

- Zoe Kinias, Associate Professor, Organizational Behaviour, Ivey Business School & John F. Wood Chair for Innovation in Business Education

- Hayden Woodley, Assistant Professor, Organizational Behaviour, Ivey Business School

- Dusya Vera, Professor, Strategy, Ivey Business School & Executive Director, Ian O. Ihnatowycz Institute for Leadership

Other ways to listen:

Q& A

During the live session on May 8, 2025, the audience members posed some questions to our faculty panel that we didn't have time to answer in the conversation. Read below for some more audience Q&A.

Q: A previous company I worked at had "We're Resilient" as a corporate value, but it almost had a subtle undertone that "it wasn't ok to not be ok" and, if you were struggling, it was on the individuals for lacking the necessary skills. How do you help corporations balance resiliency with authenticity, vulnerability, and employees being able to bring their full selves to work?

Of course, top leaders modeling a healthy culture is ideal, then it’s easier to weave throughout the organization — for example Mirvac, the Sustainable Real Estate Development company in Australia, did an amazing job with this.

If the organizational structure isn’t particularly reflective of this, Individuals and managers can also influence their own micro-cultures. It’s possible for microcultures and the individuals within them to create influence to the teams around them as well, which can have a long-term impact of shifting organizational towards a healthier collective culture.

Q: How does this work on companionship align to hybrid work?

We need to be more intentional when we don't see each other in person every day. The flexibility is such an important benefit, but the social isolation is the risk when people work remotely.

Q: Hayden, I liked your point about gathering information as a leader, but what do you do in a crisis time constrained situation?

Great question! I have a project on leadership styles during the pandemic that demonstrates that leaders that were more directive (i.e., provided clear guidance, consistent constructive feedback, progress towards goals) were seen as more effective leaders than leaders that were more empowering (i.e., delegating decision making, focusing on development and learning from errors). This supports arguments that during a crisis, a follower needs a different leadership style than during a time outside of a crisis. In fact, we found that empowering leadership was so harmful during the pandemic that it increased a desire to quit among followers.

Q: Sometimes managers intend on creating a “casual” and “informal” culture - with the intent of it addressing problematic power dynamics or strict hierarchal structures in the workplace. However, in practice, this mindset can create a culture that lacks structure, lacks processes, lacks organization, causing team members to be resilient to “make up” for this. How would an individual bring up this issue to management?

Think about sports team: they have clear roles, responsibilities, and goals that help link individual team members to the collective goal.

Having that conversation with the manager, however, is another challenge all together. There's no "one right way" to approach this conversation, since ways issues show up tend to be context-dependent. If it's an issue that impacts several team members, there's opportunity to leverage peer support to collectively approach management amd express the challenges created by a lack of structure.

Q: What would you say to a manager that suggested you focus on resiliency as part of your development plan when you push back on taking additional work for fear of the quality suffering?

Rather than framing the conversation as a refusal to take on work, it can be more effective to level set with your manager on which projects should be prioritized while remaining honest about what resources (and time is a very important resource!) should be allocated to each project while expressing what limitations may be created for the current demands you’re currently managing. This collaborative process can help both you and your manager feel closer to understanding each other and create clarity on the expected outcomes.

And not a question, but a final add in for how we should approach challenges:

What is Learning in Action?

Hosted by the Ivey Executive Education at Ivey Business School, Learning in Action explores current topics in leadership and organizations. In this podcasting series, we invite our world-class faculty and a variety of industry experts to deliver insights from the latest research in leadership, examine areas of disruption and growth, and discuss how leaders can shape their organizations for success.

Episode Transcript:

HAYDEN WOODLEY: Are you asking people to be resilient in a situation where you could actually make changes to the context to prevent them from having that resource depleted?

SEAN ACKLIN GRANT: Welcome to Learning in Action, where we explore research, ideas, and advice to help you lead and grow in business. Faced with constant disruption, leadership resilience is about staying grounded, supporting others, and showing up with clarity when it matters most.

In this special episode recorded live on Global Ivey Day 2025, we're joined by three Ivey faculty members, Hayden Woodley, Zoe Kinias, and Dusya Vera. We look at the ways leaders can build a culture of adaptability, support their people through stress, and help teams bounce back stronger and faster when things go sideways. The conversation is hosted by Bryan Benjamin. Let's get into it.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: So resilience has been a bit of a catch all, definitely a hot topic for the past number of years, and probably even more so in the past number of months. So even though there are a lot of different definitions and way of describing the term resilience and leadership, in the context of our discussion today, how would you define resilience?

HAYDEN WOODLEY: What I want to talk about a little bit is—and I guess, it's tough because I'm starting out as a classic academic and being a pessimist about this—but we have this issue where we use resiliency almost in a way as almost like an excuse.

So we'll talk about resiliency in a way like, oh, well, you seem to be more resilient, and you got to get through that and just demonstrate your resiliency. And we use this in the colloquial fashion without getting at the root of the complexity of what resilience is.

Resilience is actually a quite complex part of who we are, and it has different subcomponents to it. So often when we think about resiliency, one of the things is being adaptable. So a situation, something isn't working, instead of banging your head against the wall, can you adapt and come up with different strategies and approaches to handle that?

But often in those moments, something else that can come up is the fact that we can experience as humans lots of emotions in those moments. So we need to be able to also understand that change is difficult and it creates fear and anxiety. So that emotional regulation, understanding and not saying, I shouldn't feel that way, that's not resiliency. It's saying, hey, I do feel this way. How do I move forward with this feeling to make progress?

But that also then segues to the aspect of optimism. So how do I look at these emotions and seeing it's like, OK, do I want to view this as something threatening or something I should be feared of and feel anxious about this change? Or should I perceive this as excitement or an opportunity where I can grow and learn.

And that really gets into the optimistic side of things, and that learning gets at another component of resiliency, and this self-efficacy. And this is a near and dear to my heart area of research, but an aspect of feeling like you are capable to do something, so feeling like you can adapt, and that you can manage your emotions, and see things from an optimistic lens, that helps us feel like we have competence.

And that is a core need for us as humans—to feel like we can act as agents on our environment. But the thing is, as humans, we're not alone. We interact. We are a social species. And this is why social support is really important to surround these actions. Often, if you feel like you're banging your head against a wall, as I started off with, being able to have someone that says, hey, it looks like this isn't working for you, maybe we can try a different approach. Can I help you with that?

And knowing that we have a network around us of individuals that we can rely on to make progress. Really, those five pieces, each one of those is a giant area of research. And resiliency encompasses all of those. And that's what's really exciting about resiliency. But the problem is often if you just tell somebody to be resilient in a moment, they're like, well, what do you mean here? Do I need to manage my emotions?

Are you saying I'm not being optimistic? Are you saying, I need to adapt here? Are you saying, I don't have the right support around me? Are you saying that I'm not confident in my skills? Being able to understand and apply it more directly to the individual can be more practical. And that language around it might help us as a society get better at connecting with resiliency and being able to guide each other through it.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: Like when you give someone feedback and you say, good job, good job for what? Tell me a little bit more what are you really getting at here. So Dusya, let's bring your voice into the conversation here. And anything you'd add or build on.

DUSYA VERA: The thing is that especially the pandemic was this global situation where the word resilience started being used everyday. It's a shock. It's a crisis. It's an unexpected event. It's a discontinuous event. So the resilience came back to the table. And this muscle of how do we become more resilient.

That's why, as you said, we are all talking about resilience. And now, the last months, one more time, another type of event that is requiring us to talk about resilience. As a strategy professor, I just want to note that we also use resilience not only as individuals, like Hayden mentioned, but we also use state organizations need to be resilient.

Supply chains need to be resilient. So that also confuses sometimes. What do you mean as a person, I need to be resilient, but my company needs to be resilient, my supply chain needs to be resilient? And when we think at the organizational level or at the system level, it is more the capacity of the system to absorb a disturbance and to be able to retain its functioning.

Can we as a company absorb what is happening and then continue working and continue functioning? At the individual level, most used, I think, way to describe resilience is can we bounce back, ability to bounce back to how we were before. Others push that and say, we don't just want to be back to where we were before. We actually want to learn and grow from this, and maybe we can emerge even stronger.

So that's when people talk about can we thrive despite the adversity. So just to put that on the table, that one thing is that we are all talking about this because the pandemic taught us, I think, in many ways, to all of us to build this muscle. And we used it at the family level. Can our family be resilient, organization be resilient?

And this idea of absorbing a shock and bouncing back, thriving despite adversity and learning and growing. One last thing to put on the table is, again, I am talking about discontinuous events. There is also routine hardship. It is true. Hardship doesn't come one day, one week, one year. It could be at health level, at the family level. And that also requires our resilience muscle.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: I hear a lot of people talk about resilience, and it's got a bit of a negative-- I got to get back up, I got to bounce back. It's done to me versus I got a little bit more control. Could I use this as a way to actually spring forward? What am I learning? What am I controlling? How am I preparing?

OK, Zoe, let's get you into the conversation. What would you add on our opening question around defining resilience? And what does it mean in the context of our conversation here?

ZOE KINIAS: I think that Hayden and Dusya have already really clearly defined and given us a lot of richness for the definition. So maybe what I can add briefly to our conversation so far is that my work on resilience really focuses on keeping it simple. It really focuses on how individuals as entities and also in connection with each other, first, bring their best selves to work and, second of all, have their being enhanced.

So we sometimes think we have to control or force employees to do the best work they can do. But my work really focuses on how the being and the contributions to the organization can go together, focusing on an individual level, but this idea that when we are thriving, when we're doing the best that, when we're feeling good about ourselves and our work and our coworkers, we're doing more to contribute to our organizations and to the society more broadly.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: I'm actually going to stay with you, Zoe. Enabling each other's resilience, I'd love to hear a little bit more about some of the research and insights and maybe even contacts from organizations that you've supported around how do we enable each other. Because it's not just a, oh, my gosh, me working with me. It's part of a broader system.

ZOE KINIAS: I have a body of research on how people supporting each other enhances both their own well-being and their contributions to their organizations. And there's a couple of different focuses or foci in this context.

I'll first talk about those employees and actually all the way up to senior leadership levels. I have this beautiful data set of women and men who are very experienced managers and leaders, some of them up in the C-suite level even all over the world. So it's a really rich data set.

We use a concept that actually comes more from health psychology, and there's also some work coming from sociology and other disciplines. But this idea that other people can be there for us when we need them. And in the organizational context, we looked at how this can be supportive managers. So when you feel that your manager is there for you when you need them or that they have your back, it can be peer level. So your colleagues that you work with together on your team or who work in another segment of the organization at the same level as you. It can be supportive role models or role models that we can identify with.

And also, they can be practical, as Hayden mentioned before, so showing us how to get things done. It can be literally helping us. I have this deadline, and I don't know if I'm going to be able to make it. Can you just help me figure things out or actually do some of the work? And even just being there with each other, what the psychologists call companionate support. It sounds kind of technical, but it's this idea that we can just have a lunch break together or take a walk around the building for a stretch with our colleagues that we feel connected to and supported by. Just doing something together that isn't directly work related can also build this support.

All of these types of support, it turns out, first of all, help women to have greater workplace well-being. So they feel better at work, they feel they're able to contribute more, and they have that baseline that helps with the resiliency. When things get tough, they know that they're there for each other. So that's on the women's side.

But then the more recent paper—we published that paper in 2019—the more recent paper that we published on this is that across demographics in this sample and then in several other samples, we find that people who say they are supported by others, again, supervisors, peers, et cetera, they are more likely to do things that benefit society.

So they have done them, and they say they want to do more. And this is something that I find really exciting because it's these ripple effects or positive virtuous cycles. And we can think about if people feel isolated and alone, and it can become an inward facing type of experience for folks. But when we feel supported by others, then we're contributing to others and contributing to the organizations that we're working for and also trying to do more for society more broadly.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

DUSYA VERA: You don't have to be resilient alone, heroic resilience by yourself. It is what Zoe is saying. We can be resilient together. The connection, the collaboration. I wanted to bring up the research on improvisation and how resilience and improvisation connect. And again, we don't have to improvise alone facing either a continuous stressor or a special crisis. We can improvise together.

So research has shown that part of being resilient is the ability to pivot, the ability to be agile, the ability to say, you know what? I am going to recombine existing resources, or I'm going to recombine the plans, or I'm going to toss the plan away, and I am going to come up with something. So the ability to improvise helps us to be more resilient, because we can be more open to let go of plans.

Again, the pandemic was a great example of this when together people had to toss away their plans and help each other and build on each other's leads and think on their feet and to create something new out of nothing or to recombine pieces.

So that's an important part, that resilience is about storing stress, but it also has a relation to being agile and nimble. And for that, the ability to let go of plans and to recombine things on the go is important and helps us to feel that we can move forward, that we can bounce back, that we can thrive, we can create something new. And that doesn't have to be done alone as Zoe said. People can support each other.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: How do you let go?

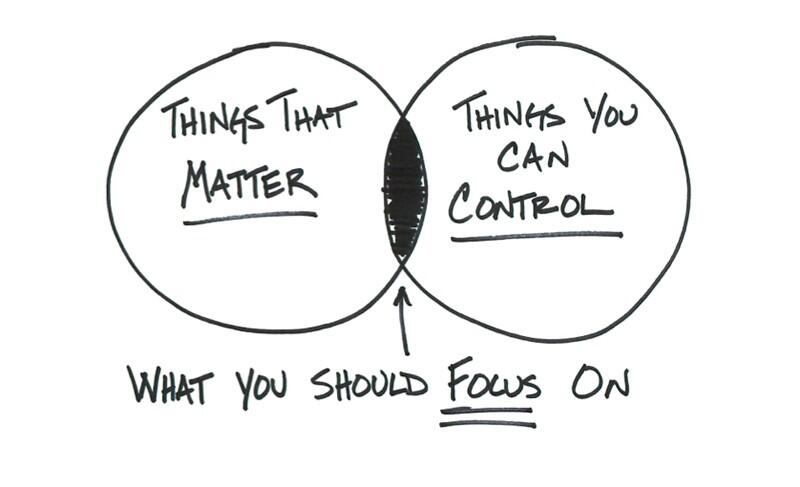

DUSYA VERA: That's something that if we go to the individual level, it starts even with that ability sometimes to accept what we can control and what we cannot. At the individual level, those moments in our lives, like personal life, professional life, when we have to say, what can I control and what can I not control? So I have to understand that, I have to accept this is what I can control and not.

So we let go sometimes when we manage to accept that things have changed. Change is continuous. Hayden said change is hard. Change is hard and continuous. And when we manage to see our plan, it doesn't fit anymore. We can try to force it to fit. The conditions are not under control anymore. That's when we manage to let go and say, there is something that we can recombine here.

So I think that moment, it's very hard, Bryan, of course, to say, we had this idea in our mind, and now, we are not at the control of the conditions and things have changed.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: Absolutely. If we think about when the pandemic first hit, it's like, yeah, I had an in-person program running the very next week. It's not going to happen. I've got no control. What can I control within that context?

So Hayden, the role that an organization plays and we hear about resilience as one of our core values and potential pros and cons with that, as well as resilience almost to an extreme where the risk of someone burning out might factor in.

HAYDEN WOODLEY: This is an area that I have a pretty strong pet peeve with, especially because as someone who specializes in teamwork. How many times do you see an organization say they value teamwork, but then they have an environment where they only give compensation for individual performance? They don't give feedback to the team. They don't select people and ask them what they can bring to a team environment and to their role.

They often say it performatively and not with true commitment to what it actually means. And resiliency has the same challenge. If you really want to invest in resiliency is the aspect of: are you asking people to be resilient in a situation where you could actually make changes to the context to prevent them from having that resource depleted?

So yeah, sometimes a client changes something or wants something to be done differently, that's unexpected, and you can't necessarily control that. But I think it was in 2024, mistreatment cost the US economy an estimated $914 billion. That's something where you can't ask people to be resilient because they have an abusive supervisor, or they're allowing colleagues to treat each other and then forcing someone to use up their resiliency to survive.

Why don't we remove that from the environment and allow people to perform at their best? One of the things I often do, and to drive this point home, and I know we can't really do this here, but I say, raise your hand if you want to suck at your job. And nobody has ever put their hand up once.

So why are we focusing on trying to push someone to perform at their best within the constraints of their context and not focus on allowing people to use their resiliency and their motivation to push towards the success that they want to feel like they have? As you work in organizations, it's not always easy to have this broad impact and make change but find out where you can make that change.

Because as core to this, and as Dusya and Zoe have already spoken about, is the power of this social support. If you provide somebody else social support, you're actually helping that person be more resilient. We're not alone in these contexts. So it's not always just about us. It's also about how we can start creating norms that support the resiliency of others.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: It's like when you're talking, Hayden, I think about someone's really upset or anxious and the manager says, calm down. Chances are someone's not going to calm down because someone said, calm down. It's like, let's actually dig into what's going on, what can you control, what's maybe at a more systemic level that we need to pay attention to do.

Dusya, leader character, I know, is a topic near and dear to you and the Leadership Institute, and there's been phenomenal research and really great work going on there. So let's talk about it as an enabler for resilience. So we think about it at an individual level, we've hit on some of the systemic pieces. But let's look at an individual level. And if you could elaborate a little bit more about the role that leader character plays and how it factors in.

DUSYA VERA: As you mentioned, leader character is an expertise of the Leadership Institute and at Ivey. We're very proud that we help our students to be competent and to be committed but also to understand the importance of developing who they are and who they are is their character.

We talk about resilience at Ivey and Ivey programs to our students as one behavior of character and a behavior actually of courage. It's part of being courageous and dealing with challenges and adversity. Resilience is part of that. We also explain to our students that resilience, like Hayden mentioned, you could overdo it. It's a vice of excess.

You're trying to be resilient all the time. And then of course, there could be a deficiency of resilience where you actually feel fragile, and you feel like you don't know what to do with all these challenges. And maybe you feel like you cannot even move. You're paralyzed.

So there is a balance of resilience in being able to manage adversity and manage challenges. But to actually be at that balance, we need other dimensions of character to support us, to build on us. So for example, the temperance, the calm to be able to see the big picture, to not rush.

Resilience is also about being able to (inaudible) what is happening? Let me take a moment to breathe and analyze the situation. Situational awareness, the judgment to know, like Hayden mentioned, the judgment to know when to be resilient and when to actually-- resilience means pushing the system to be resilient, to actually push and try to change things, not just adapt myself.

The humility, again, the self-awareness to see how am I reacting to my daily stressors and how I am reacting to shocks and the transcendence to have a purpose, to have a future orientation that gives meaning to the resilience. So yes, this is hard. We can do hard things. There is a meaning for this moment when I have to practice my resilience.

In addition to all our research and programming on character, we recently had the opportunity to also work with University of Pennsylvania and their Positive Psychology Center. And actually, the three of us were part of some workshops really to dive into resilience, a skills and resilience toolkit.

So that is something that we're excited, that we really think Ivey students, MBAs, HBAs, all of our students, executives are very interested in that muscle. And so we are learning even more things to add to our own research to be able to incorporate that in programming.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: Thank you for commenting on that. It isn't just about coming out of school with the knowledge and the skills. If someone is faced with a situation where they need to put their resilience to the test, whether it's bouncing back or pushing forward, I really like how you're talking about taking control where you can and proactive.

It's why it's so important to us at Ivey. We want to get that well-rounded leader, and you feel like resilience, and if someone can come out with an understanding of what it is and a jar of tools and tricks that they can apply. We've been going to the gym. We're exercising that muscle. It gets a little easier once you start to go consistently and use it consistently. I want to hear from Zoe and Hayden as well on this individual resilience.

ZOE KINIAS: Some of my research has shown that people are more able to be resilient, particularly in those very challenging environments when they believe that their own core personal values are welcomed by the organization. So someone within the organization in a position of power says, we care about your values. We want to hear from you about those values. And that can enable those who are particularly likely to be vulnerable due to demographic characteristics to feel that they don't need to worry about the potential stigmatization or demographics.

At the same level, your values matter to us. We want you to bring those in, can be beneficial. And I'm going to just say that first. So that's a way of incorporating this. But I don't want to stop there because what Hayden was saying earlier is so, so important, that that is the buffering resiliency by living by our own personal values.

And actually, I can share a couple of examples of this. Many of us have in mind someone that we know or someone that we've seen in popular media that is a person who's made it against the odds. And I'm not going to throw names out there because you'll have your own mental representation. And I don't want us to end up getting focused on the particular examples that I share.

These might be political leaders, these might be business leaders, but those individuals, if we look at their behavior, and we look at how they talk about their lives, those who have made it against the odds-- and I'm not talking about being set up for success demographically, financially, how they were raised, everything. These people so frequently have a strong connection to living by their values.

We see this. It's like, how did they do this? And you ask them, what do you do when things get tough? We're just about to publish a case on a fantastic health care leader in the United States, and for her, it's her connection to her religion is very, very important. And she'll say that I live according to the values of my religion. And she's not pushing it on her employees. She's not doing anything like that, but she is embracing them and she is living in accordance with them in her personal and her professional life. So I think that that's just the little tidbit that I can add on our conversation here.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: Over to you, Hayden.

HAYDEN WOODLEY: Often, I think, socially, I think, leaders who are vulnerable, are bad, and we don't really that's not how behavior you should demonstrate and relating to Dusya is talking about leader character. Character actually is about embracing vulnerability and building relationships and trust.

I have a project with a colleague, and one of the things that we desire the most in leaders and in followers is a feeling of trustworthiness. And to get that trustworthiness, it takes vulnerability. It's nice when a leader says to me, "I know you're having a hard time with this right now. I've had a hard time with that too. Here's something that worked for me that helped me get through that."

There's social support being provided, efficacy being addressed, emotional regulation being addressed as well, trying to give someone to be adaptable. And you're getting optimism in that. So it's this simple little action a leader is doing that can really help someone develop their resiliency.

And I think what becomes really important is—I call this help conundrum — is helping people the way they need to be helped versus helping people the way we want to help them. I find that to develop resiliency among your group, you need to be able to recognize the difference between the two.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: So let's say, I'm an employee and I divulge what I'm struggling with. We can have an interaction and a conversation. What if you as a manager are spotting something and the employee isn't actually forthcoming for whatever reason? Any tips and tricks for how we can get a manager to get an employee to open up, for lack of a better word, so that they might be able to be supported?

HAYDEN WOODLEY: Often, a shorter version of it is I talk about taking an alternative approach to these conversations, and the A-L-T in alternative is capitalized. And by saying, you should ask and then listen to the answer, which often we don't. We ask a question but mostly to hear what we want to hear and already moving in the direction we want to go but truly listen to what they say. And by acknowledging it and making sure you understand it and then trying to move towards a solution.

And often that is a linear process, but it also happens in a cyclical fashion. So if you try something and it doesn't work, don't be like, well, what's wrong with you? This is what you need to do. Ask again, well, why wouldn't that work for you? And then listen and then try again. And this iterative process can seem time consuming, but it's a good investment to get a truer understanding of where the person's at.\

Because it's true. Humans are not good at assuming things about people. We think we're really good at predicting someone's personality, and we think we're good at knowing how smart somebody is. But that correlation is nowhere near as strong as we hope it would be.

And related to that, the average human being thinks they're above average driver, which doesn't make sense. We have this challenge of, well, why don't we approach this less from the aspect of I know what to do and I'm going to push towards a decision and instead, I'm going to try to gather information, which aligns well with this knowledge based economy that we're in, where I describe leaders as gatherers of information and not hunters of decisions.

And this becomes really important in a situation like this, because you can't know everything. You can't be all the things all the time. You need to be able to say, how do I get the information I need to make a good decision. And that's where I would levy some of that effort towards is developing a good process of engaging in a structured way of having those difficult conversations in a resilient way.

People are also more accepting of decisions when they feel like their voice was heard towards it, even if the decision was, yeah, your idea was terrible and wrong. I would prefer that than just being like, well, nobody listened to my idea. And that's why this asking, listening, and then trying in this iterative process can be really advantageous to handle those conversations.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

BRYAN BENJAMIN: Given how broad our topic is and far reaching it is, and something that we haven't necessarily rarely talked about yet, so you can introduce something new, a new dimension. Or maybe there's a next level to something that we've scratched the surface on.

DUSYA VERA: One thing that we have touched so far, but I think we can go a little bit further is resilience is universally considered a positive virtue. But also, of course, there are conversations where there is this expression, call me resilient, call me resilient, call me fool. Are you asking me to accept everything to always-- I have to be able to manage everything within different contexts.

And we have started to analyze things from different contexts, especially with minorities. There is this feeling, why am I always the one who has to be resilient in this context? So I wanted to bring that in. I know Zoe and Hayden are passionate about this topic, so I just wanted to see if we could touch that.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: Zoe, Hayden.

ZOE KINIAS: Hayden, I hope you don't mind me sharing that you're an excellent baseball player. So I had the visual of you actually hitting it home there at the end for us. There's a couple of things that I wanted to share. First, I want to bring us back to this idea that I think Hayden and Dusya both brought up, that we might have this mistaken idea about resiliency just being tough all the time.

One analogy that someone explained for many, many years ago, and the visual is so strong for me that I'm going to share it with you today, is that if we think resiliency is just holding it all down, try to imagine being in the swimming pool. It's starting to warm up a little bit in the swimming pool or at the beach and holding a beach ball under the water. So I'm pushing it down. I'm pushing it down, pushing it down. And as soon as I'm not paying attention, I'm exhausted. There's COVID disruption or another disruption. It's going to spring out. Or maybe I'm just tired and hungry and whatever it is, it's going to pop out, and then it makes an explosion for everyone.

But if we can practice that taking care of ourselves and doing the soft release, it's like letting it bounce up a little bit in a controlled way, then we don't get so exhausted with that. And it doesn't become so difficult to manage. And having some release valves, I think, is really important and encouraging people to find ways to do that.

So that's the very, very individual level that I wanted to build on what folks were sharing before. And then thinking about the system change. An element of this that I've been thinking about a lot lately is that everyone who's trying to improve society needs to be resilient.

And so it's not an either/or, either be resilient or change the system. And related to that, one of the things that I get really excited about is when we see people more than those who are just disadvantaged within a system really striving to improve things. So people who are already empowered, people who are already having the ability to have great influence. Those are the people we most want engaging in shifting systems and improving systems to make them more equitable, to make them more humanitarian, to make them more humane.

And so when we think about that, even if we're powerful within our organizations or demographically members of groups that disproportionately are empowered, it's tough to change systems. And so being resilient and drawing on those resiliency resources for that work is something that I really encourage.

BRYAN BENJAMIN: Hayden.

HAYDEN WOODLEY: Building on what Zoe and Dusya have mentioned, I think there's a connection that we all see in the fact of this misconception of what resiliency is. And I would argue, yes, it's a really, really helpful resource. One of the things that's really interesting I actually find is an area of occupational health psychology that talks about differentiating between demands in the workplace and the resources available in the workplace and how being able to balance those become really important.

And then resiliency fits in as more of this personal resource that you bring into that environment. And being able to and understand your context from like, what are the demands that are being placed on me? And what resources do I have available to me to deal with those demands can help structure, I think, an understanding of where resiliency is needed and/or where resiliency might be wanted.

And one of the things that I think I'm trying to distinguish between is the challenge I have is if I see someone demonstrating resiliency, they're being adaptable, I see them managing their emotions. I see them trying to be optimistic, see them relying on, OK, I can do this. And maybe I'll talk to some of my friends and get some advice from them. I start to immediately think, what's going on here that's causing this person to have to do that?

And I think it becomes really important, and one of the things that shaped my career path, I used to want to be a lawyer, but while working, I experienced something called fundamental attribution error, where we as humans have a tendency to assign things to the person in the context and not understand the situation that transpired.

And that to me has been fundamental for me pursuing the things that I've done from an academic standpoint but also from a practical standpoint, because too often, we want to blame other people. So you need to be more resilient, or you got to work on your resiliency and develop that resiliency. Say, well, why are we depleting that resource?

I get that through controlled training and development, we might be able to replenish that resource. But that's a big ask. And it's often we ignore the context and say, well, what can we change here so that people can use their resiliency for the unpredictable events that will transpire and less for things that we've created in our environment that are preventing people from having these opportunities?

I know Zoe also talked about this from a discrimination standpoint, and that's one of the challenges. We talk a lot about when you see successful marginalized individuals. They talk about how they've used resiliency to get where they've gotten to. And it's like, well, that's not good, right? That's an inequity. Right.

Any time from the perspective of is that person getting the appropriate outcome based off of the effort they're putting in, I think understanding that and seeing, oh, well, that person is putting in more effort to get the same, that's not fair.

Why are we asking them to be more resilient than that other person? And how can we make changes to how we operate to reduce those mistreatments? Give people opportunities to demonstrate their capabilities and not have them struggling trying to push this beach ball hold up below water.

These situations, I think, what connects all of this aspect of how we can start viewing our world from the context of what's the stressor and not how do we deal with the stress.

SEAN ACKLIN GRANT: Thank you for tuning in to Learning in Action. We'd like to thank our guests, Hayden, Zoe, and Dusya. Learning in Action is produced by Rachel Jackson, Joanna Shepherd, and me, Sean Acklin Grant. Editing and audio mix by Carol Eugene Park.

If you liked this episode, make sure to subscribe. You can also find more information by visiting IveyAcademy.com or follow us on social media at Ivey Academy for more content, upcoming events, and programs. We hope you'll join us again soon.

Note: This article was originally published under our former name, The Ivey Academy. We are now known as Ivey Executive Education.

About Ivey Executive Education

Ivey Executive Education is the home for executive Learning and Development (L&D) in Canada. It is Canada’s only full-service L&D house, blending Financial Times top-ranked university-based executive education with talent assessment, instructional design and strategy, and behaviour change sustainment.

Rooted in Ivey Business School’s real-world leadership approach, Ivey Executive Education is a place where professionals come to get better, to break old habits and establish new ones, to practice, to change, to obtain coaching and support, and to join a powerful peer network. For more learning insights and updates on our events and programming, follow us on LinkedIn.