This is the final post in a four-part blog series on Regulating Ontario’s electricity sector. The series was motivated by my participation in a panel discussion on regulation at the APPrO 2018 Canadian Power Conference. Panellists offered views on how to improve the electricity sector’s regulatory framework.

In this series, I explore three related issues that are fundamental to our understanding of effective regulation:

- Why regulate?;

- When should government delegate authority to an arms-length regulator?; and,

- How should this authority be prescribed to the regulator?

In considering these issues, I discussed the rationales for regulation (public interest versus public choice) and two principles for effective governance (subsidiarity and separation between regulator and government). In this post, I draw on these concepts to suggest reforms to Ontario’s regulatory framework in the public interest.

The current landscape

Ontario’s electricity sector has evolved considerably since the Electricity Act, 1998. The Act has been amended 59 times and at least once per year since 2004. These amendments have gradually expanded the government’s role and centralized planning, and reduced reliance on competitive market forces and market-based mechanisms.[1]

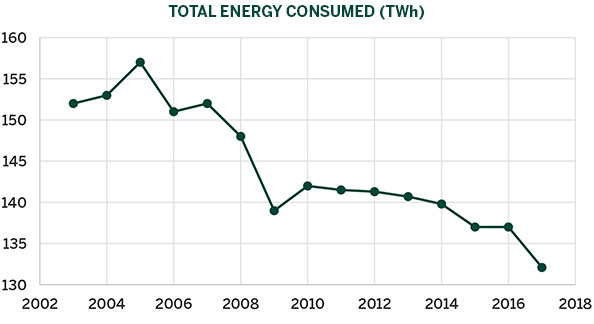

Figure 1: Ontario’s Changing Supply Mix and Demand Patterns

Source: Author created from data available from the IESO

From a structural perspective, the supply mix has changed considerably with the shutdown of the coal facilities and the addition of nuclear, renewable energy, and natural gas resources. Ontario’s consumption patterns have changed since the start of the 2008 recession. Total annual energy consumed and peak hourly demands have declined at the transmission-level. This is in part a lingering effect of the recession, but also a product of the province’s initiatives around energy conservation/demand management and the shift towards distributed energy resources.

This evolution has been both positive and negative.

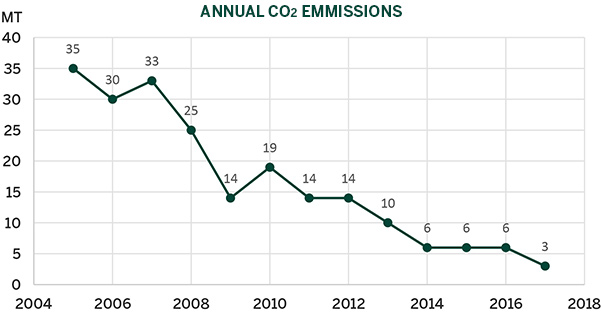

Figure 2: Carbon Emissions and Resource Adequacy

Sources: Author created from data contained in IESO 2018 Technical Planning Conference Presentation

On the positive side, Ontario has reduced its carbon emissions from the electricity sector over the last several years. In 2017, more than 95 per cent of the electricity generated in Ontario was emissions free. Furthermore, the IESO indicates there is an adequate supply of resources to reliably meet projected peak demands for the next five years.

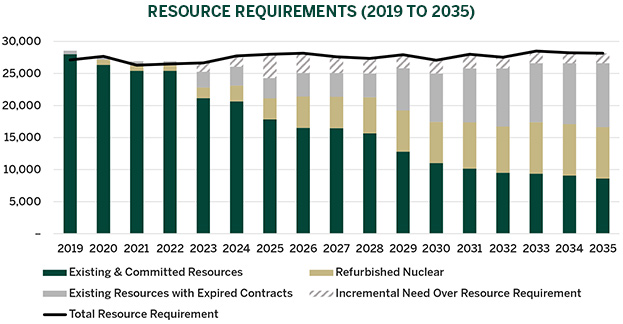

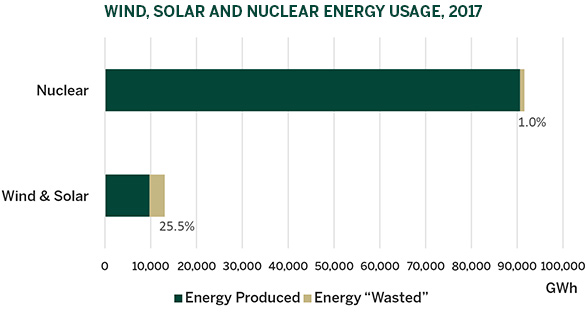

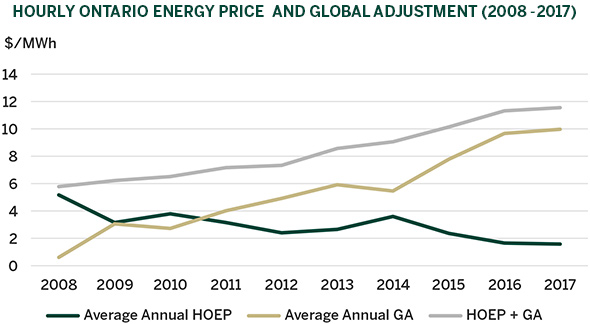

Figure 3: Surplus Emission-Free Generation and Increasing Electricity Costs

Source: Author created from data available from the IESO

On the negative side, several public reports, including those cited in my previous post, Regulating Ontario’s electricity sector, show evidence of wasteful and inefficient expenditures incurred through an ineffective and poorly governed electricity planning process.[2] For example, there are many periods in the year when Ontario produces more emission-free energy than it consumes. It then sells electricity to neighbouring jurisdictions at a lower price than paid to the electricity producers on guaranteed contracts. Ontario consumers bear the difference in cost. On many occasions, hydroelectric generators, wind generators, and even nuclear generators have had to spill or “waste” emission-free power due to insufficient demand. Furthermore, the average unit cost of electricity has increased considerably over the last several years, at least in part due to this wasteful and inefficient expenditure.[3]

In moving forward, Ontario is challenged to realize the positives for the system, but at a lower overall cost and with less waste. For its part, the IESO with its Market Renewal initiative, is moving towards a greater reliance on competition and market-based mechanisms to drive efficiencies, innovation, and private investment. The new Minister of Energy, Northern Development and Mines, Greg Rickford supports this initiative. At the APPrO Conference he said he “was confident that IESO’s Market Renewal initiative and its incremental capacity auction will lower costs and increase efficiency.”

Regulatory reform in the public interest

The electricity sector’s regulatory framework – its legal, procedural, and institutional arrangements – is large and complex. Detailed suggestions for regulatory reform are beyond this blog’s scope. Instead, I offer suggestions at a macro level, based on the premise that Ontario residents want a regulatory framework that serves and protects the public interest, rather than the short-term private interests of elected officials, civil servants, or special interest groups (i.e., a public-interest rationale for regulation). I focus on regulatory options at the wholesale level (i.e., IESO governance and its functions, including OEB oversight of the IESO) as this is where most of the criticisms of poor governance and its effects on system costs have been placed. I do not consider more detailed regulatory reforms for the OEB (i.e., how it is governed, how it regulates local electricity distribution companies, how it manages hearings, etc.). These issues will be addressed in the soon-to-be-released OEB Modernization Panel report.

Finally, I presume the province will place greater reliance on the use of competition and markets to guide consumption, production, and investment decisions in the sector and that options for regulatory reform should align with this. With these working assumptions, I offer the following suggestions to recalibrate the current regulatory framework to better promote the public interest.

- Clarity of the IESO’s legislative mandate

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) produced a 2014 report with best practice principles for regulatory agency governance. At the top of the list is role clarity. Role clarity is essential for an agency to understand and fulfill its mandate effectively. In particular, the OECD report recommends the objectives and functions of an agency should be clear to the agency and the broader public. The agency should not be assigned conflicting or competing objectives or functions, unless there is a clear public benefit from doing so, and a prescribed means for the regulator to effectively and transparently manage the risk of conflict. Furthermore, assigning principle-based rather than prescriptive objectives, allows the regulator to apply its expert discretion in complex and dynamic environments, where appropriate, to derive optimal regulatory solutions that are consistent with the objectives.[4] However, the objectives should be defined with sufficient precision so as to limit the scope of the agency’s interpretation of its powers to avoid the risk of regulatory “mission creep.”

Over the last several years, the IESO’s mandate has blurred relative to that of the Ministry of Energy and the government more broadly. This is a result of successive amendments to the Electricity Act, 1998, which establishes the IESO and its mandate. For example, the number of IESO objectives prescribed in the Electricity Act have nearly tripled since 2002 – the year the wholesale electricity market opened, growing to 20 from seven in 2002.

In 2002, the IESO’s (then Independent Electricity Market Operator, or IMO) core mandate was to promote an efficient, competitive, and reliable market. The objectives of efficiency and competition reinforce that competitive markets, when functioning properly, lead to efficient outcomes. Promoting an efficient and competitive market can also support reliability, although the market rules have always been clear that in the event of a possible conflict, the IESO is to give “precedence” to reliability.[5] The IESO’s original mandate was clearly defined and logically consistent.

Under current legislation, the IESO no longer has a mandate with respect to promoting competition. Its objectives still make reference to efficiency and reliability, but have expanded to include: promoting the use of cleaner energy sources, supporting the system-wide goals for the amount of electricity to be produced from different energy sources, facilitating load management, promoting conservation, and assisting the OEB in facilitating rate stability for certain customer classes. Further, as stated in the purpose clause of the Electricity Act, the IESO should pursue these objectives in a “manner consistent with the policies of the Government of Ontario.”

The IESO’s pursuit of its new objectives around preferred technologies, load management, conservation, and price stability may at times conflict with or come at the expense of the efficiency mandate.

Furthermore, it’s not clear how the IESO effectively resolves potential conflicts between efficiency and the other target-based objectives, except to say they are to be managed in a “manner consistent with the policies of the government,” and generally under the direction of the government through its adopted oversight of the long-term energy planning function.

The upshot is the IESO’s mandate under the Electricity Act is now broadly defined by the government’s prevailing policies. Experience tells us government policies are subject to change at any time depending on the political imperatives of the government of the day. Arguably, this makes the IESO’s mandate less clear now (to the IESO and the public) than it was at the time of market opening. And as the reports I cite above have indicated, this has come at the cost of economic efficiency and higher rates for consumers.

2. Promoting economic efficiency is in the public interest

As I discussed in “Why regulate Ontario’s electricity sector,” competitive markets, which harness the self-interest of individuals through the “invisible hand,” lead to the best use of society’s scarce resources (i.e., economic efficiency), and in so doing, promote the public interest at large. Government or regulatory intervention is justified only when there is evidence of a failure in the competitive market to achieve the most efficient ideal outcomes. Furthermore, as I note in “Delegating regulatory decision-making in the electricity sector,” the subsidiarity principle proposes government should delegate regulatory responsibility of economic efficiency matters of the public interest to expert, arms-length, unelected regulatory agencies, such as the IESO. Public interest issues of equity and wealth redistribution should be left to elected government officials and implemented mainly through the broad-based tax and transfer system rather than through subsidies to preferred technologies or consumer groups.

A case can be made that the IESO should return to its original mandate with the strict focus on the promotion of an efficient, competitive, and reliable market. First, as discussed above, this would provide the IESO with a clear and logically consistent mandate. Second, the economic efficiency mandate, when clearly defined, confines the relevant evidence and lends itself to objective tests such as cost-benefit analysis. Overall, this insulates the technical experts within the IESO from the pressures of the private interests of stakeholders or government officials, and empowers them to make the best choices in the public interest. Finally, electricity is an important contributor to the long-term growth of the Ontario economy. Ensuring the sector operates efficiently will improve the economy’s productivity and promote growth in overall per capita living standards in the province; Ontario’s citizens will be better off.

3. Separation of powers between the IESO and government

Separation of powers between agencies and government is important for a public-interest approach to regulation. While the IESO derives its objectives and legislative mandate from the government, it needs independent responsibility over this mandate to allow for transparent, impartial, and fact-based decision-making, insulated from short-term political calculus. Transparent, impartial, and fact-based decision-making promotes public trust and confidence in the agency and the regulatory decision-making process. Public trust and confidence in the IESO’s decision-making process and operation of the market is of particular importance going forward, if the province is to place a greater reliance on competition and markets to encourage investment in risky, long-lived energy infrastructure (see more on this below).

A clear separation of powers requires the removal of Ministerial directive powers over the IESO from the Electricity Act. These directive powers increase the possibility that regulatory intervention will occur for short-term, private, or political objectives as opposed to the public-interest objective of economic efficiency. The IESO must implement the Minister’s directives. The directive powers clearly limit the IESO’s ability to assess whether the directive is in the public interest as per its legislative mandate. For example, a directive to negotiate and enter into an electricity trade agreement between Quebec and Ontario undermines the IESO’s ability to assess the economic efficiency of the agreement relative to alternatives. It also undermines private investors’ confidence in the integrity of the competitive process as the means to encourage the retention or investment in new assets.

4. Independence of government balanced by effective accountability and transparency measures

The flip side of the separation of powers and independence is accountability and transparency. The OECD report recommends comprehensive measures holding the agency accountable to the legislature or another responsible authority be instituted to ensure the agency does not exceed its powers when exercising its independent decision-making authority. The OECD report also stressed open and transparent decision-making. Decisions based on evidence or research and made with stakeholder input, build confidence and trust in the decisions and the decision-making process more generally. An open and transparent decision-making process reduces the risk of actual or perceived influence from self-interest groups or the private incentives of the agency and its staff. Public confidence and trust in the agency are reinforced if the right to appeal the agency’s decisions is extended to members of the public where their standing is recognized by a judicial authority. The right to appeal should be allowable on the grounds that the agency exceeded the powers attributed to it, provided insufficient consultation, or omitted important information in making its decision.

If the government were to delegate the IESO independent decision-making authority over economic efficiency matters related to the operation of the grid and market, it would be prudent to review the effectiveness of the accountability and transparency measures currently in place.

For example, a clear separation of powers would require the government to relinquish its current involvement in long-term electricity resource planning and procurement, and to delegate that to the IESO. The IESO would have the independent authority to choose a resource planning and procurement method in accordance with its legislated mandate, which I argue should be to promote economic efficiency and reliability. The IESO may choose to use a capacity market, a competitive tender and contract, or some alternative method to identify and procure sufficient resources to ensure it achieves its reliability planning standards as efficiently as possible.

But how could the government ensure the IESO is held accountable to its legislated mandate in making this decision? One option is to require the IESO to seek OEB approval of its planning and procurement method. As part of the approval process, the IESO would be required to include an evidence-based cost-benefit analysis that establishes the reliability need for the resources and the relative efficacy of the chosen procurement method compared to alternative methods. The OEB would hold a public hearing to allow interested parties to present evidence on the matter, confined to the technical merits of the IESO’s cost-benefit analysis. Through this adjudicative approach, the IESO would be held accountable by the OEB and the public to its mandate.[6] The legislature would also have a transparent means for assessing the IESO’s performance vis-a-vis its mandate. This option would be consistent in spirit to the requirement that was originally placed on the former Ontario Power Authority with respect to its Independent Power System Plan. Alberta has adopted a form of this adjudicative approach for the approval of the Alberta Electric System Operator’s capacity market rules. American ISOs have similar obligations under the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to prove changes to their market rules (tariff) meet the FERC’s “just and reasonable” standard.[7]

Making the IESO more accountable to the Market Surveillance Panel (MSP) is another option. The MSP oversees the IESO by monitoring and identifying flaws or inefficiencies in the operation, design, and overall structure of the market. The MSP reports its findings semi-annually to the OEB and where appropriate, recommends to the IESO remedies to address the identified flaws and inefficiencies. Currently, the IESO is not obligated to act on these, although the Chair of the OEB requests the IESO provide a response to the MSP’s findings and proposed remedies. Through this informal process, the MSP, beginning in 2002, has frequently reported inefficiencies with the original “two-schedule” design of the IESO energy market, recommending the IESO look to implement a single-schedule design that provides better locational price signals and promotes more efficient outcomes. The IESO has generally agreed with the MSP’s findings and recommendations on this issue, and from time to time explored a single-schedule design with stakeholders.[8] For various reasons, it never resolved the issue. Only now, with apparent government support and stakeholder acceptance, is the IESO seriously following up on the MSP recommendation for a single-schedule design in its Market Renewal initiative. Arguably, this is evidence of the IESO’s failure to deliver on its efficiency mandate since market opening.[9]

To strengthen the IESO’s accountability to the MSP and to its efficiency mandate, the MSP could be given in legislation, the right to appeal to the OEB the IESO’s responses to its findings and recommendations, requiring both the IESO and MSP to provide a cost-benefit analysis in support of their respective positions. Again, the hearing could be open to the public to provide evidence confined to the merits of the IESO's and MSP's cost-benefit analyses. This would give the MSP a clearer mandate to seek resolution of unresolved issues. It would also foster greater transparency and responsiveness around the issues. It would make the IESO more accountable to its efficiency mandate.[10]

The benefits of a public-interest approach

In this post I have argued that providing the IESO with a clear economic efficiency mandate, and delegating independent decision-making authority to the IESO for this mandate subject to effective accountability and transparency measures, would increase the potential for transparent, impartial, and fact-based decision-making, particularly with respect to electricity planning and resource procurement. It would foster public trust and confidence in the decision-making process and the IESO market operations.

Improved public trust and confidence in IESO decisions and the market is particularly important if the IESO is to put a greater reliance on competition and markets to attract and retain private investment. It matters to achieve the full benefits projected under the Market Renewal initiative.

The current public choice approach to regulating the Ontario electricity sector is causing what economists call ‘hold-up’ risk for investors. Hold-up occurs when the government issues directives or implements policies after an investment has occurred, that make it unprofitable. When there is a risk of hold-up, investors will choose not to invest or require contractual security with above-market rates of return to protect against hold-up. This ultimately leads to higher costs for consumers and a less efficient economy. In more extreme situations, this could also compromise reliability.

This point was noted by the IESO consultants, the Brattle Group, when assessing the potential benefits of the Market Renewal initiative, particularly with respect to the implementation of an incremental-capacity auction. The report notes “Ontario’s power system operates in an environment of regulatory risk that is arguably higher than in many other jurisdictions” and “(n)ew investors evaluate the risk of regulatory interventions when assessing the attractiveness of entering a market; prices will need to be higher or locked in for a longer period to attract investments into a market with substantial regulatory risks.”[11]

The report recommends:

“(t)o maximize the benefits to Ontario and minimize regulatory risks …Ontario will need to carefully evaluate its own policy environment, governance structure, and interactions with clean energy policy in order to develop a well-designed incremental capacity auction tailored to achieve the needs of the province cost-effectively.”[12]

Final thought

Ontario would be better served by a public-interest approach to electricity sector regulation. A public-interest approach based on economic efficiency would require elected officials to relinquish their powers to intervene in the electricity sector to control short-term market outcomes. History shows this is unlikely. Elected officials have generally over-managed the system in the short term rather than trust the agencies will protect the public interest over the long term. There are several reasons, not least of which is the public perception that governments have the power to control the outcomes in the sector. The four-year election cycle puts pressure on governments to produce results quickly, even if not in the long-term interests of Ontario electricity consumers or the Ontario economy at large.

Real reform of the regulatory framework requires the public and elected officials to recognize the public interest is best served by taking a consistent efficiency approach to the sector instead of using the sector as an instrument for wealth redistribution or short-term political gains. Resisting the temptation to over-manage the sector is a tough ask, but real reform in the public interest requires it.

[1] In 2004, the very first purpose in the Purposes Clauses of the Act, “(a) to facilitate competition in the generation and sale of electricity…” was removed and the name of the system and market operator was changed from the Independent Electricity Market Operator to the Independent Electricity System Operator (emphasis added).

[2] Additional reports that highlight inefficient expenditures due to ineffective governance include Michael Trebilcock’s CD Howe report, Ontario’s Green Energy Experience: Sobering Lessons for Sustainable Climate Change Policies, August 2017, and former Ontario Auditor General, Jim McCarter’s 2011 report.

[3] See Ivey Energy Centre Policy Brief, The Economic Cost of Electricity Generation in Ontario.

[4] Readers interested in learning more about best practices in the design of regulatory agencies may also want to read Guy Holburn’s Ivey Energy Centre Policy Brief, Regulating Mega-Projects: The Case of Muskrat Falls.

[5] Chapter 5, section 1.1.3 of the Market Rules.

[6] To be effective, the OEB staff and Board members would have to have the requisite knowledge and technical expertise and be provided sufficient financial resources to assess and critique the cost-benefit evidence.

[7] The U.S. approach is discussed in more detail in a report written by CRA for the Alberta Department of Energy.

[8] Since market opening, the IESO has reviewed options to replace the two-schedule system on four occasions. See slide 13 of http://www.ieso.ca/-/media/Files/IESO/Document-Library/engage/me/ME-20160419-Market-Development-Retrospective.pdf?la=en.

[9] George Vegh posited an interesting question in the APPrO panel discussion. In reference to the expected efficiencies to come from Market Renewal, he asked: ‘Why was this not the IESO’s day job over the last 15 years? The things that we’re talking about — single-schedule market or day-ahead market — these have been on the agenda for more than 10 years.”

[10] Accountability could be further strengthened by making the MSP a stand-alone agency independent of the OEB. This is the model used in Alberta and PJM Interconnect. The benefits of this model are discussed in more detail in a report written by CRA for the Alberta Department of Energy

[11] The Brattle Group, “The Future of Ontario’s Electricity Market: A Benefits Case Assessment of the Market Renewal Project”, Report to the IESO, at page 12 and page 70.

[12] The Brattle Group, “The Future of Ontario’s Electricity Market: A Benefits Case Assessment of the Market Renewal Project”, Report to the IESO, at page 73.