This blog is the first in a series written by Ivey HBA student, Alyna Liu, who is currently researching the effects of flaring and venting regulation in Alberta and Saskatchewan’s oil industry.

Canada has set ambitious CO2 emissions reductions targets: by 2030, the Government hopes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40-45% relative to 2005 levels. Yet, these goals are confronted with the still growing emissions from the oil and gas sector.

Between 2000 and 2018, emissions from Canada’s oil and gas sector increased by 23% (NRCan, 2020). Of course, much of this increase in emissions was combined with a growing contribution to Canada’s economy. Still, notwithstanding this economic contribution, there is a prominent source of emissions – flaring and venting of natural gas at well-heads – that provides little economic value and whose environmental effects remain poorly understood (Agerton, Gilbert and Upton Jr., 2020).

The Province of Alberta has a long history with flaring and venting. This blog outlines several milestones in this history and provides background, a “pre-history”, on the development of the province’s flaring and venting regulation. A subsequent blogpost digs into the province’s current rules and regulations around flaring and venting and their development.

What is flaring?

Start with the basics. What is flaring? There are two types of flaring: irregular and regular flaring. Irregular flaring is used for emergency safety and worker protection, while regular flaring is used as a disposal method for unwanted natural gas, a waste product in oil production referred to associated gas (Agerton, Gilbert and Upton Jr., 2020). Both regular and irregular flaring waste resources – natural gas is typically a valuable source of energy – and are environmentally damaging (e.g., by releasing greenhouse emissions and other pollutants into the atmosphere). Thus, flaring, especially regular flaring, is something of a puzzle. Why would oil and gas firms dispose of a valuable resource and what can be done about it?

Agerton, Gilbert and Upton Jr. (2020) outline four reasons why firms flare and vent, attributable to physical and regulatory constraints:

- The infrastructure (pipelines, field compression) to capture and transport gas has yet to be built

- Existing midstream infrastructure is too small (i.e., there is a lack of capacity at gas processing facilities)

- Flaring gas is cheaper than building the infrastructure to collect and transport gas

- Safety measures to protect workers

Provincial rules have successfully helped push the industry to reduce flaring but have not eliminated the practice entirely. To obtain a handle on the practice, new rules must acknowledge the reasons why firms flare. But before discussing the existing rules and regulations, and the push to eliminate flaring and venting, this post examines its history – and the history of the natural gas industry more broadly – in Alberta.

Alberta's pre-history timeline [1]

Alberta’s natural gas industry first launched in 1883 with a discovery in the Southeast part of the province (CAPP, 2021). From these initial wells, it took more than 50 years to establish any official regulations and protocols on well flaring and venting, and more than a century to establish maximum flaring and venting volume regulations.

Prominent landmarks in Alberta’s early natural gas industry include:

- 1883: Discovered natural gas at Langevin; well is drilled near Medicine Hat, Alberta

- 1891: The Canadian Electrical Association is formed to represent the electric industry

- 1901: The first commercialized gas field is developed in Medicine Hat

When the Alberta’s natural gas sector was first developing, the greatest concerns were protecting equipment and smell, not the potential negative externalities (Bott, 2004).[1] However, natural gas is naturally odourless, with scent usually indicating the existence of impurities or manually added with the purpose to become distinguishable at sites. Debates around odour highlight how, even at the turn of the century, there was little understanding of the economic and environmental consequences of the burgeoning natural gas sector.

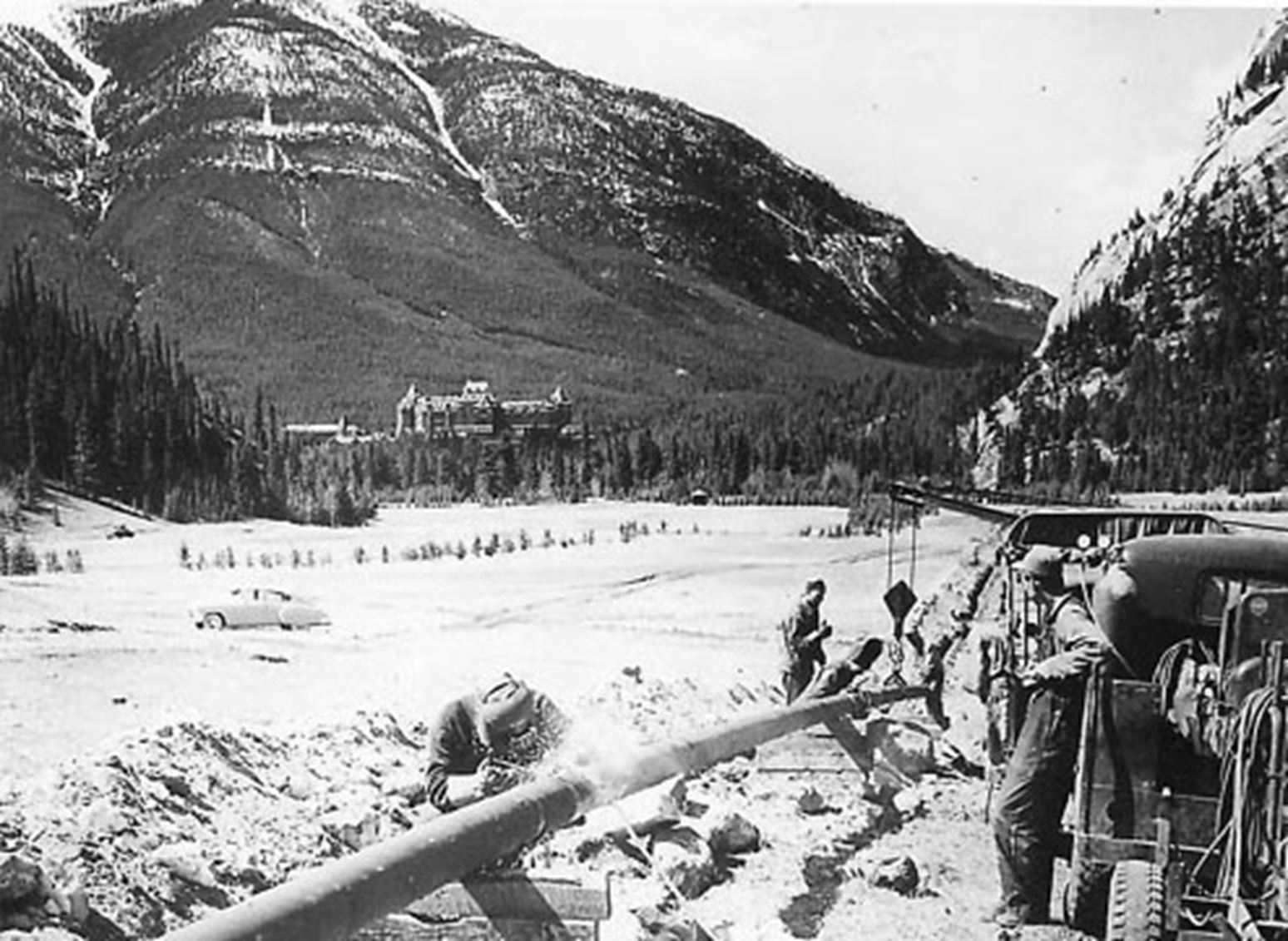

Prior to the construction of early gas processing plants, all excess gas in Alberta was flared or vented. Other developments in Alberta’s gas industry include:

- 1910: The City of Calgary starts to use natural gas for home heating

- 1912: A 275 km pipeline from Bow Island to Calgary is built by Canadian Western Natural Gas replacing coal for heating, lighting, and cooking fuel

- 1913: Gas becomes widely used across Alberta towns

- 1914: First discovery of gas-condensate reservoir at Turner Valley

- 1923: Edmonton converts to natural gas (discovered in 1914 but delayed due to the war)

- 1925: Processing plant to remove H2S from natural gas built in Turner Valley, AB

- 1930: Canadian federal government transfers control of natural resources, including oil and natural gas, to provincial government of Alberta through the Natural Resources Transfer Acts

Although Alberta became a province in 1905, the federal government still retained control over natural resources until 1930. This is when the power transferred to the provincial government through the Natural Resources Transfer Act. Shortly following the passage of this law, the first attempt to regulate the industry in Alberta was made. In 1933, the Turner Valley Conservation Act came into effect, legislation whose goal was to manage future development. However, the Act did not allow the province to exert control or influence over companies with existing contracts with the federal government. Thus, the majority of companies remained unaffected. With the onset of the Great Depression and increased litigation from the oil industry, early regulatory pushes faded. Overall, Alberta’s first attempt at regulating flaring and venting failed.

Landmarks in the history of Alberta’s energy industry include:

- 1933: Turner Valley Conservation Act put in place to regulate future companies

- 1936: Discovery of oil column in Turner Valley starts to change controversy surrounding flaring regulations

- 1938: Alberta Petroleum and Natural Gas Conservation Board formed by Social Credit Government—significantly reduced flaring of natural gas as by-product of oil production

- 1950s: Promotion of natural gas as a safe, clean alternative to coal

Natural gas saw its second boom – and the second boom of flaring and venting – during the 1950s post war period. Gas was marketed as a safe, clean alternative to coal (Alberta Energy, 2020)[2]. Prominent highlights, including attempts to curtail flaring or venting during this period, in this period include.

- 1951: TransCanada Pipelines first incorporated—starts construction

- 1952: Turner Valley and Jumping Pound begin converting H2S in sour gas to benign elemental sulfur—Largest exporter of sulfur in the world (Alberta, 2021)[3]

- 1957: First gas exported to Eastern Canada by TransCanada Pipelines

- 1971: Creation of first environment ministry in Canada—stringent regulations first start; Oil and Gas Conservation Act receives assent, marking the start of regulations to eliminate flaring, venting, and incinerating

- 1972: Energy Resources Conservation Board decision determined pool production accuracy standards of 2.0% for oil, 3.0% for gas, and 5.0% for water

It is only in 1971, with the creation of the first environment ministry in Canada through the Department of the Environment Act, that rules and regulations are introduced to start eliminating flaring, venting, and incinerating (Hermis, 2021)[4]. However, the newly enacted regulations will not come into effect for well over 20 years later. The following year, in 1972, the first ever pool production accuracy standards are implemented by the Energy Resources Conservation Board, now known as the Alberta Energy Regulator, the sole regulator of Alberta’s energy sector. This marks the turning point for regulations in the natural gas industry and the onset of modern environmental regulation in the province.

- 1980s: Vertical oil and gas wells no longer used exclusively with the advent of horizontal drilling

- 1980: Gas Resources Preservation Act receives assent

- 1982: Amoco Dome Brazeau 13-12-48-12W5 blew out creating a stink across Alberta; first public outcry

- 1983: Mines and Mineral Act receives assent

- 1985: Rules and regulations for measuring oil, gas, and flaring are established with Directive 017

- 1985: Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and the federal government sign the Agreement on Natural Gas Markets and Prices, staring the process of natural gas price deregulation in Canada (NRCan, 2020)[5]

- 1993: Creation of Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act for Alberta

- 1995: Alberta’s Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB) changed name to Energy Utilities Board (EUB)

- 1996: CAPP sets first baseline of max flaring per year at 1340 106 m3/year with utilization rates targeting 91-92%

1983 marked 100 years since the first discovery of natural gas in the province. Two years later, in 1985, the rules and regulations for measuring oil, gas, and flaring are established with the creation of Directive 017 and the Agreement on Natural Gas Markets and Prices is signed by the federal government. However, this is still 11 years before the first maximum baseline for flaring is established.

This sets the stage for Alberta to meaningfully introduce rules and regulations regarding flaring, venting, and incinerating. These rules will be discussed in the next blog post.

Sources

https://www.bakerinstitute.org/media/files/files/03160f6a/ces-agerton-etal-naturalgas-072420.pdf

http://history.alberta.ca/energyheritage/gas/transformation/regulation/flaring.aspx

https://www.capp.ca/natural-gas/history-of-gas/

https://csegrecorder.com/articles/view/a-brief-history-of-canadas-natural-gas-production

https://www.alberta.ca/alberta-energy-history-up-to-1999.aspx#jumplinks-0

https://hermis.alberta.ca/paa/Details.aspx?ObjectID=GR0053&dv=True&deptID=1

http://www.energybc.ca/cache/oil/www.centreforenergy.com/shopping/uploads/122.pdf

[1] Note: all timeline landmarks were collected from http://history.alberta.ca/energyheritage/gas/transformation/regulation/flaring.aspx, https://csegrecorder.com/articles/view/a-brief-history-of-canadas-natural-gas-production, https://www.aer.ca/regulating-development/rules-and-directives/directives and https://www.alberta.ca/alberta-energy-history-up-to-1999.aspx#jumplinks-0 unless otherwise indicated

[2] http://www.energybc.ca/cache/oil/www.centreforenergy.com/shopping/uploads/122.pdf

[3] http://history.alberta.ca/energyheritage/gas/transformation/default.aspx

[4] http://history.alberta.ca/energyheritage/turner-valley-gas-plant/history-of-the-turner-valley-gas-plant/challenging-times/the-provincial-government-and-conservation.aspx

[5] https://hermis.alberta.ca/paa/Details.aspx?ObjectID=GR0053&dv=True&deptID=1

[6] https://www.nrcan.gc.ca/energy/energy-sources-distribution/natural-gas/frequently-asked-questions-about-natural-gas-prices/5685